The Deadliest Marksman’s Cold, Brave Stand

November 5 | Posted by mrossol | Europe, History, InterestingSource: The Deadliest Marksman’s Cold, Brave Stand

Eighty years ago, a freezing Finnish farm boy took aim at the unstoppable Red Army — and became the greatest sharpshooter the world has ever seen.

- Michael Stahl

Read when you’ve got time to spare.

Photos courtesy of the Finnish Military Archives.

The war was nearly over on March 6, 1940. The enemy, propagandized as an unstoppable fighting machine, was indeed overwhelming the army of the country they’d invaded. Six days later, the aggressors would finally force an armistice, and soon grab control of much of the land they’d coveted. It had taken longer than the two weeks they’d anticipated, but conditions were harsh, the defenders far more resolute than expected. For more than three months, battlefields roared with motoring tanks, gunfire and artillery explosions, obliterating the natural beauty of the countryside. Through it all, one warrior emerged as perhaps the finest killer in military history, on a mission to serve his besieged nation by picking off foreign attackers — many, many of them — one by one with a sniper rifle.

On that afternoon in March, however, Simo Häyhä of Finland was out of his element. Instead of scheming in a snowbank behind his sniper rifle, camouflaged in white, hundreds of feet from a target, he was part of a squadron in counterattack mode against Russian soldiers, who were at times just a few yards away — and possibly too scared to go home without a victory. After the Russians had been pushed back for a time, they reemerged with a furious charge. A shot rang out, and suddenly Häyhä was on the ground, bleeding profusely from his face, the grisly victim of an exploding bullet that had been banned by most nations. According to one account of the battle, while unconscious, with his left upper jaw blown away completely and his left lower jaw cut in two, Häyhä was placed in a pile of bodies killed in action. Later, a fellow soldier, looking for Häyhä on orders from his commanding officer, noticed a leg twitching among the grim grouping. So began Häyhä’s 14-month-long recovery from the wound that, even after 26 surgeries, would leave his face disfigured for life.

The Russian troops had snuffed Häyhä out of the Winter War, which had begun on November 30, 1939, but not before he had compiled, by some accounts, a kill count in excess of 500 by sniper rifle, more than anyone in recorded history.

* * *

Born on December 17, 1905, Simo Häyhä, the second youngest of eight children, grew up on a farm near what is now Finland’s southeast border with Russia. At the time, however, Finland was under Russian rule. When he was a young boy, his father took him hunting for elk, deer, moose and birds in the isolated countryside. He also enjoyed skiing and other sports. It was a completely ordinary life for a young man from the region.

At age 17, four years after Finland gained independence from Russia, Häyhä joined the Finnish Civil Guard and quickly established himself as a highly regarded marksman, winning several shooting competitions.

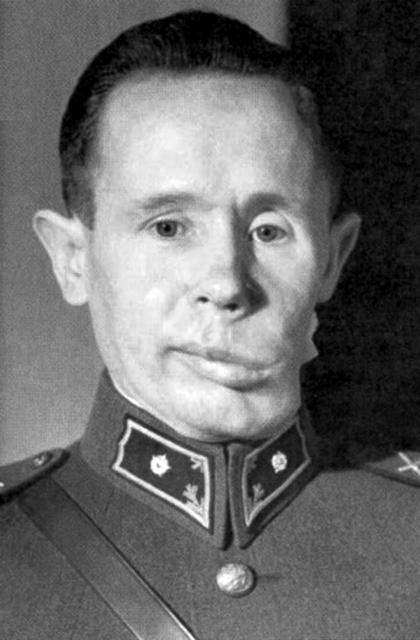

Portrait of Simo Häyhä after being promoted to second lieutenant, 1940. Häyhä was disfigured after being shot in the face by a Russian soldier.

“Everybody knew him as good with the rifle,” says Lasse Laaksonen, an adjunct professor of history at three Finnish universities. Laaksonen observes that it “was no miracle” that Häyhä became such a skilled sniper. By the time the Winter War broke out, shortly before Häyhä’s 34th birthday, he’d amassed well over two decades of experience in shooting, often waiting patiently in the Scandinavian cold and snow for an animal target to present the perfect opportunity to strike.

“He knew the anatomy of the battlefield; he knew how to be quiet in the forest and how to handle the situation when the temperature was very low,” Laaksonen says.

His firearm of choice was a Finnish-modified Mosin-Nagant M1891 rifle, which was originally manufactured in Russia. The Finns nicknamed their version the “Pystykorva,” their word for the spitz breed of dog, because its foresight guards were reminiscent of the canine’s pointy ears. It was the Finnish army’s preferred rifle, in part because it rarely jammed, and also because the stocks were made of Arctic birchwood, which was not susceptible to warping in the cold.

According to one story among the many that comprise the Häyhä legend, during his Civil Guard training, he once hit a target 16 times from 500 feet away in just one minute. “This was an unbelievable accomplishment with a bolt action rifle, considering that each cartridge had to be manually fed with a fixed magazine that held together five cartridges,” wrote Tapio Saarelainen in his biography of the marksman, The White Sniper: Simo Häyhä. A former member of the Finland armed forces, Saarelainen added: “For those of us who consider ourselves well-trained marksmen today, such a feat would be impossible to attain however long we trained.” (One rifleman YouTuber, having heard the Häyhä tale, tried to pull this off and came up well short, hitting the target 15 times but taking nearly two minutes to do so.)

In 1939, Stalin ordered the attack on Finland, seeking territory that might buffer his Soviet Union against an impending onslaught from Hitler. Stalin’s invaders opened up front lines across the entire border. He had more than a million troops under his command, and they imposed themselves on a Finnish army about one-third the size.

In the months leading up to the Winter War, with the Russian threat imminent, Häyhä was called to serve again and taught fellow soldiers how to shoot like him — though, ultimately, none could raise themselves to his level.

A Finnish soldier in position on the ground during the Winter War, 1940.

During the Winter War, Häyhä was stationed on the Karelian Isthmus, a stretch of land where the bulk of the bloodshed occurred. The isthmus is only 70 miles across at its widest point, and the border region had few roads. The Russian tanks moved best atop established roads, so the Finns knew precisely where they were coming from. Russian companies that didn’t stick to the roads found themselves in unknown, densely wooded areas where mobile Finnish forces, jetting into the battlefield on skis, used guerilla warfare tactics to hit their enemy hard and retreat quickly, deeper into the forest.

Finnish snipers like Häyhä, sometimes with a spotter in tow, would take a position in the snow around dawn, and then wait hours for targets to emerge. “Simo always dressed up very warmly,” says Vesa Nenye, co-author of Finland at War: The Winter War 1939–40. Häyhä wore heavy coats with fur interiors and oversized gloves, all in white. This enabled him “to remain comfortable for long periods of time, stalking the enemy, while the padded clothing can also offer further stability when taking aim.”

In addition to the camouflage, Häyhä hid his position from the Russians by pouring water over the snow where he rested the muzzle of his rifle. The snow would then freeze — the coldest winter temperatures ranged between -4 and -20 degrees Fahrenheit. When Häyhä fired his Pystykorva, there would be no puff of snow for the Russians to see. Häyhä also put snow in his mouth, keeping his breath cold enough to eradicate the condensation cloud that would otherwise appear. And though Häyhä once disclosed that he killed soldiers from as far away as 1,400 feet, he used only his firearm’s foresights, never mounting a scope on the rifle, out of fear that his enemy might notice the sun’s glare in it.

Simo Häyhä, right, and Colonel Svensson, who awarded Häylä a rifle and a certificate for his contribution to the Winter War, 1940.

When Häyhä shot one of their comrades, the Russians bombarded the area where they thought he might be located with artillery. They just never happened to hit him.

Häyhä was active through all but the last week of the 105-day Winter War, and his reported sniper kill count stands at either 505 or 542, an average of five per day, with a reported single-day high of 25 dead. Some say the total count was even higher, while others claim it was likely less. Laaksonen, the Finnish military history scholar and a former member of the Finnish armed forces, calls the 500-plus sniper kill figure “optimistic.”

“I think the number is about 200,” Laaksonen says, observing that kill counts of most of history’s snipers are exaggerated. “I have [researched] the guns, the snipers, the battlefields, the troops in different areas of the battlefields, and I think 200 is the most true.”

A representative of the Finnish museum that bears Häyhä’s name says there are some “official war diaries” that also estimate a kill count of “200-plus” for Häyhä. However, the museum also displays a recently discovered memoir believed to have been written by Häyhä, which says that he killed more than 500 Russians. A representative of Finland’s National Archives wrote in an email, “Unfortunately, it is not possible to find such detailed information related to Soviet losses” in the Winter War.

Further clouding the history is the long-established ambiguity behind what a “confirmed kill” actually is. Chris Kyle, author of the memoir American Sniper, said in an interview with Time that scoring a confirmed kill requires “witnesses verifying that [the enemy] is dead,” while former Navy SEAL sniper Brandon Webb told NBC News, “It’s one of those things that’s more on the honor system.” Since Häyhä usually went out shooting alone, his kills appear to mostly be self-reported. If Häyhä inflated the numbers, however, it would betray the humble, unassuming disposition he otherwise appeared to have had. (Reportedly, when he was once asked how he became such an outstanding sniper, Häyhä simply replied, “Practice.”)

Nenye counterargues that “The figures above 500 kills are highly realistic.” According to him, notes from the Finnish novelist Mika Waltari, who visited the Winter War front lines a couple weeks after the hostilities began, confirm as much. Waltari was told Häyhä was already at 138 confirmed kills, and “the company commander had started to keep official records and assigned special observers to keep track of Simo as soon as he was mounting up [an] average of 10 kills a day,” Nenye says.

* * *

As spring neared on March 12, 1940, defeated Finnish leaders signed the Moscow Peace Treaty, ending the Winter War. One day later, Häyhä regained consciousness for the first time since being shot in the face and nearly left for dead a week earlier.

Though Finland’s forces fought valiantly — and effectively, having lost around 22,000 men to Russia’s 120,000 casualties — they could not stand up to Russia’s resources over the long term. The Finns “didn’t have enough ammunition,” says Timo Myllyntaus, a professor of Finnish history at the University of Turku. By March the Finnish army was undernourished, with supply chains faltering, and overtired. “Also, Finland was afraid that the winter was ending … and they knew that in summer conditions the Soviet army [was going to be] much stronger.”

Häyhä after being awarded the honorary rifle, model 28, 1940.

Finland ceded nearly 10 percent of its land to Russia in the peace treaty. As the World War II front lines broadened in the early 1940s, Finland aligned itself with Fascist Germany. Myllyntaus says that some historians believe the Finnish government hoped that if Germany defeated the Soviet Union, Hitler would return control of the territories ceded in the Winter War back to Finland. “If Stalin had not taken almost 10 percent of the Finnish territory after the Winter War, I think the Finns would have preferred to stay neutral,” Myllyntaus says.

Hitler, said to have been encouraged by the Red Army’s struggles in Finland, launched an invasion of Russia on June 22, 1941. Three days later, a second war between Finland and the Soviets broke out, the Continuation War. Germany provided Finland military support, as well as much-needed grain to feed its hungry population, and fossil fuels, according to Myllyntaus.

Finland and Germany made great advances into the Soviet Union, but as German resources eroded, the Soviets battled back, pushing out both armies. The Continuation War ended in September 1944. Its corresponding peace treaty stipulated that Finnish forces eject all German soldiers from their country. Finland also gave control of all of the territories it had taken during the Continuation War — including those it had lost in the Winter War then recaptured — back to the Soviet Union.

Finland never again recovered the land it lost, and 400,000 refugees from those regions fled for other parts of the country. Häyhä himself was one of them. His family farm was on land that Russia gained in the peace treaty, according to Nenye, the history writer. After leaving a military hospital in May 1941, Häyhä settled near Utula — a village about 40 miles west of his hometown and the new border with Russia.

Häyhä shooting at the Simo Häyhä Sniper Competition in Sotinpuro, Finland, 1978. Photo courtesy of Tapio Saarelainen.

He ran a farm for much of the rest of his life, living alone, quietly, never marrying or having children. He lived to be 96, dying of natural causes in a veteran’s facility.

Despite killing hundreds of men, there is no evidence that his mind suffered the kind of scarring his face had endured.

“Reading through his wartime diary or subsequent frequent interviews, it seems he found some peace,” Nenye says.

For his Häyhä biography, Tapio Saarelainen asked him if he ever had nightmares about the Winter War. “I am a happy and fortunate man,” Häyhä responded. “I have always slept well, even during battles on the front.”

Häyhä even had a bit of gallows humor about the whole bloody affair. In one interview, he was asked if he’d met any Russian veterans since the Winter War had concluded. Häyhä said that he hadn’t met any Russian soldiers in the intervening years, but wryly added: “During the war I did meet many, but those I did did not survive.”

Michael Stahl is a freelance writer, editor and journalist based in Queens, New York, whose work has been published in many print and digital publications, including Rolling Stone, Vice, Vulture, Village Voice, Mic, Quartz, and CityLab. He is a contributing editor and the layout manager at Narratively.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.