Financial Retirement “Rules”

February 12 | Posted by mrossol | American Thought, EconomicsWorth considering some different perspectives on the subject.

=====

WSJ 2/10/2018 by Anne Tergesen

When saving for retirement, calculate your “number,” the amount you’ll need without running a big risk of depleting your savings. When in retirement, spend no more than 4% of your initial balance, adjusted annually for inflation.

And when investing in retirement, start out with a relatively high percentage in riskier assets like stocks and increase your exposure to safer bonds as you age.

These are some long-held rules that most retirement scholars and financial advisers espouse.

But with both stocks and bonds expensive by historic measures, and people having longer retirements, researchers are rethinking these rules to better manage the risk of a market decline.

“Retiring now is pretty dangerous,” says David Blanchett, head of retirement research at research firm Morningstar Inc. “No one knows what will happen in the future, but among those who make forecasts, there is an expectation for lower returns.”

Here are ways in which three retirement-saving tenets are changing:

The 4% rule

Conventional wisdom says you can withdraw 4% from your savings in the first year of retirement and give yourself an annual raise over the next 30 years to keep pace with inflation without a significant risk of going broke.

For someone with a $1 million portfolio, the formula produces an initial income of $40,000 and—assuming inflation of 2.5%—an increase to $41,000 in year two.

But in recent years, the rule’s safety has been questioned. While 4% would have worked over every 30-year retirement from 1926 on for an investor with 60% in large-company stocks and 40% in intermediate-term U.S. bonds, it failed in almost half of the simulations researchers recently ran using forecasts of future, rather than past, returns.

As a result, “3% is the new safe withdrawal rate,” says Wade Pfau, a professor at the American College of Financial Services in Bryn Mawr, Pa., who ran the numbers with Mr. Blanchett and Michael Finke, also of the American College.

What should you do if you want, or need, to spend more than 3%?

Consider a dynamic approach, Mr. Blanchett says. Many dynamic strategies set their initial withdrawal rate for a 30-year retirement at about 5%. But they require users to cut spending in a year in which their portfolio loses value.

One simple example calls for forgoing inflation adjustments following any year in which your investments sustain losses. The downside: Inflation-adjusted income is likely to decline over time.

A second method, dubbed “the guardrail approach,” provides more latitude to raise spending.

Say you retire with $1 million in a portfolio with 60% in U.S. and foreign stocks and 40% in bonds and withdraw 5%, or $50,000, in year one. At year-end, you must recalculate your withdrawal amount as a percentage of your new balance. Assuming your portfolio declines to $800,000, your $50,000 withdrawal—plus an annual adjustment for inflation— now represents more than 6% of your new $800,000 balance.

Any time your withdrawal rate rises above 6%, the rule imposes a 10% pay cut for the next year,

says Jonathan Guyton, a financial adviser and co-creator of this strategy. As a result, after adjusting the $50,000 initial withdrawal— to $51,000, assuming 2% inflation—the method imposes a 10% pay cut, of $5,100, to produce a $45,900 withdrawal in year two.

The good news: You can take a 10% raise following years in which your withdrawal rate falls below 4%.

In years in which your withdrawal rate is between 4% and 6%, simply adjust your most recent withdrawal—$ 50,000 in this example— to keep up with inflation.

(But don’t take the inflation adjustment following any year in which your investments lose money.)

Find your ‘number’

This rule calls for amassing a specific dollar amount, such as 10 times your current salary, before retiring. But that can be dangerous, says Mr. Blanchett.

Why? During a bull market, your balance may rise enough to tempt you to save less or retire early, setting you up for trouble if the markets reverse course.

A better approach, Mr. Pfau says, is to avoid looking at your balance and focus instead on saving a consistent amount annually.

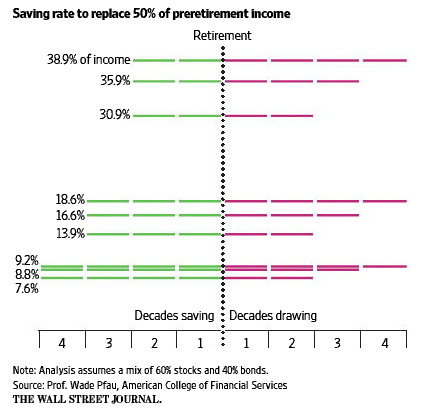

Mr. Pfau recommends that someone with 30 years until retirement and a portfolio with 60% in stocks and 40% in bonds save about 16.6% of their annual income a year.

That would have been high enough to replace half of preretirement income over the past 150 years, even amid poor stock-market returns.

Stick to glide path

According to the conventional wisdom, people just entering retirement should have a significant portion of their savings—say, 40% to 60%—in stocks to help their nest egg increase. As they age, most should gradually reduce their stock exposure to protect against market de- clines.

But a recent study by Mr. Pfau and Michael Kitces, director of wealth management at Pinnacle Advisory Group Inc. in Columbia, Md., finds that those who take the opposite approach—by reducing stock exposure in the initial years of retirement and then gradually raising it over time—are likely to make their money last longer.

According to the research, those who start retirement by reducing their stockholdings to 20% to 30% of their portfolio and end up with 50% to 70% in stocks can withdraw 4% of their balance a year and give themselves annual raises to compensate for inflation over 30 years, even in the worst market scenarios. (The authors based these simulations on historical market returns rather than accounting for the lower interest rates facing today’s retirees.) In contrast, those who keep 60% in stocks throughout retirement or who taper to a 30% stock allocation from 60% are likely to run out of money after 28 years in the 5% of worst-case scenarios, says Mr. Pfau.

Of course, if stocks fare well in the early part of retirement, those who use the conventional approach will come out ahead. But the new approach provides better downside protection in the years right after retirement, when retirees are most vulnerable to financial losses. If a bear market occurs then, a portfolio can quickly be depleted by market losses and withdrawals.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.