100,000 Missing Women – Part 1

November 29 | Posted by mrossol | Abortion, Social Engineering

SEOUL—A cultural preference for male children has cost Asia dearly. Count up all the girls who were never born because of selective abortion, victims of infanticide and females who died from neglect and there are upwards of 100 million women missing on the continent today by some estimates.

Not just a human-rights catastrophe, it is also a looming demographic disaster. With Asian birthrates already plummeting, that is tens of millions of women who will never be mothers. The economic and social impact on some of the world’s largest countries is incalculable.

For decades, South Korea was Exhibit A in this depressing trend. By 1990, as medical advances made prenatal sex selection routine, the ratio of male-to-female babies soared in South Korea to the world’s highest, at 116.5 males for every 100 females.

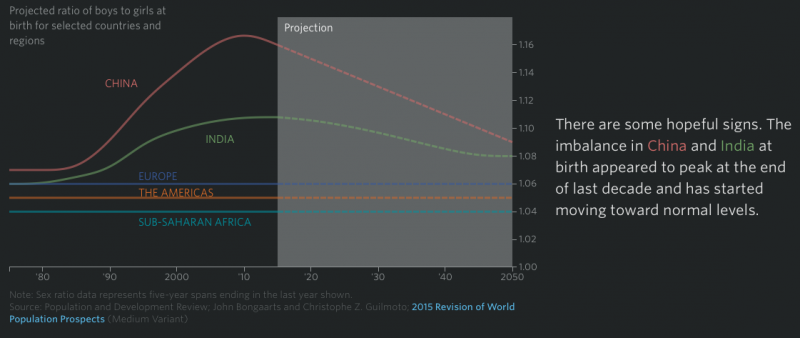

There are some hopeful signs. The imbalance in China and India at birth appeared to peak at the end of last decade and has started moving toward normal levels.

Then something unusual happened. South Korea did a U-turn.

In one generation, South Korea has gone from a society where sons are prized to one where daughters are just as eagerly received. Turbocharged industrialization, urbanization and education, along with a feminist revolt, wiped out centuries-old practices in which a son was essential to inherit property, worship ancestors, care for parents and continue the family lineage.

By last year, the country’s gender ratio had recovered to a normal 105 males born for every 100 females.

The dramatic transformation offers important lessons for Asian giants China and India—one-third of humanity that continues to give birth to significantly more males.

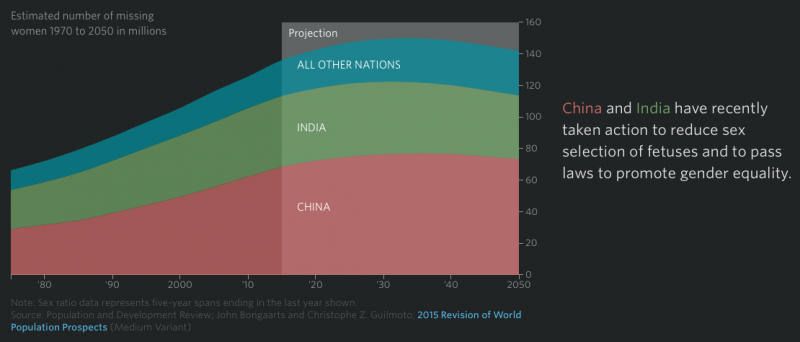

China and India have recently taken action to reduce sex selection of fetuses and to pass laws to promote gender equality.

In these countries that together hold 2.7 billion people, vast numbers of men won’t be able to find brides in the coming decades, obliterating universal marriage, the underpinning of socioeconomic organization for centuries.

Having so many unattached, alienated men could have potentially devastating economic and social consequences. Some social scientists fear that incidences of rape and bride trafficking in parts of Asia could be early effects of the skewed sex ratios here.

One study by Lena Edlund at Columbia University and others suggested a causal link between a more masculine sex ratio and crime, analyzing province level crime data in China to show that a single point rise in the sex ratio of men aged 16 to 25 raised property and violent crime by between 5% and 6%. China has seen a dramatic increase in crime between 1992 and 2004, and the Columbia study attributed as much as one third of that rise to the increase in the maleness of the young adult population. The theory, in part: Unmarried men are more likely to commit crimes than married men, especially as they try to accumulate assets to compete for scarce brides.

“I don’t see any good consequences—I see only misery and desolation,” says Christophe Z. Guilmoto, a demographer at the French Research Institute for Development in Paris.

The intellectual debate over this misalignment has a long history. In 1990, Amartya Sen, the Nobel Prize-winning Indian economist, shocked the world with an article in the New York Review of Books that estimated there were 100 million missing women because of discrimination.

Since then, demographers have devised more precise methods of calculating missing women in each country. They factor in the toll caused by malnutrition and poor medical care and, more significantly, also the numbers lost to abortions of female fetuses, a problem recognized in the years after Dr. Sen wrote his article.

In June of 2015, the Population Council, a New York City-based research organization, published a study saying there were 88 million missing women world-wide in 1990, when Mr. Sen wrote his article, and that there were 126 million missing in 2010, roughly half of them attributable to prenatal sex selection. Of those, more than 112 million were in Asia.

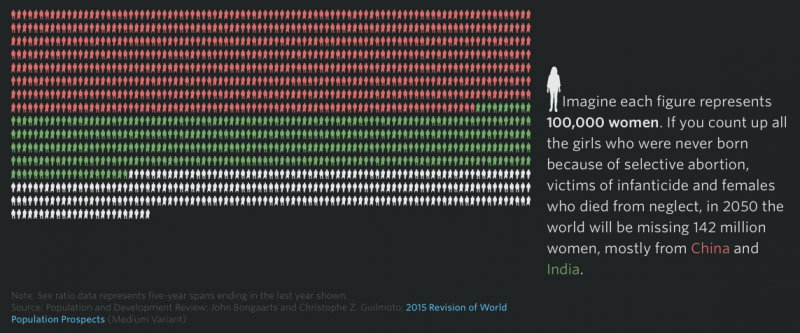

Imagine each figure represents 100,000 women. If you count up all the girls who were never born because of selective abortion, victims of infanticide and females who died from neglect, in 2050 the world will be missing 142 million women, mostly from China and India.

The paper, by John Bongaarts, a distinguished scholar at the Population Council, and Dr. Guilmoto, projects an increase to 150 million missing by 2035 and then a slight decrease to 142 million by 2050.

Across Asia, the effects are only beginning to be felt as the first generation born with skewed sex ratios in the 1980s and 1990s reaches marriageable age.

In Korea, nearly 10% of marriages in 2005 were made up of a Korean husband and a foreign wife, mostly from China, Vietnam and the Philippines.

But as the marriage squeeze worsens in the next few decades, no amount of bride migration will be able to stem the shortfall, demographers say.

The problem will “intensify radically in the next five years and become explosive in the next decade,” says Nicholas Eberstadt, a political economist and demographer at the American Enterprise Institute in Washington who studies sex ratios.

If the masculine sex ratios remain as high, in China, there would be as many as 186 single men for every 100 single women hoping to marry by midcentury, according to Dr. Guilmoto, since unmarried men from one year join the next year’s group seeking wives. By 2060 in India, the peak could be higher: 191 men for each 100 women.

http://www.wsj.com/articles/asia-struggles-for-a-solution-to-its-missing-women-problem-1448545813

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.